ORIENTAL CARPETS

At Prayer [1855-1935] by Ludwig Deutsch

The senses jolt to the fiery grades of saffron, potent curry powders, and dreamy lavender.

With a simple gesture, vendors offer coffee and tea just outside their treasure trove of antiques, jewels, and works of art. Here, hospitality is KING.

Their magnetic aura, hypnotizing warmth, and welcoming smiles bear a striking resemblance to characters you were once introduced to, long ago, in a childhood story book.

Endless colors line the walls, lanterns light the maze-like paths, and four thousand shops co-exist to make up the world’s most enchanting and intricate marketplace — Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar.

BEWITCHED, you venture inside to discover endless treasures, one more inciting than the next. The greatest purchase one can make, however, is that of an oriental carpet.

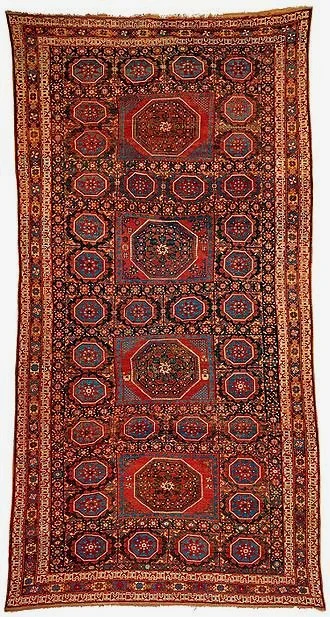

Egyptian Carpet 1500s

The Carpet Merchant of Cairo (1869) by Jean-Leon Gerome

Fame Fortitude Rug (1668)

Cyprus trees for immortality, lilies for purity, peony for wealth, carnation for wisdom, and Tree of Life is for eternal paradise.

These are just some of the floral designs incorporated in the making of oriental carpets.

Animal designs include lions for victory, elephants for power, peacocks for divine protection, camels for wealth, crabs for invincible knowledge, and doves for peace, butterflies for happiness.

From the warmest hues - reds, browns, golds – to the cooler ones – greens and blues – colors also represent deeper meaning.

Red for happiness, orange for devotion, yellow for power and glory, and brown for fertility. Whereas the cooler tones depicted include greens for paradise, blues for truth, black for destruction, and white for peace, purity, or grief.

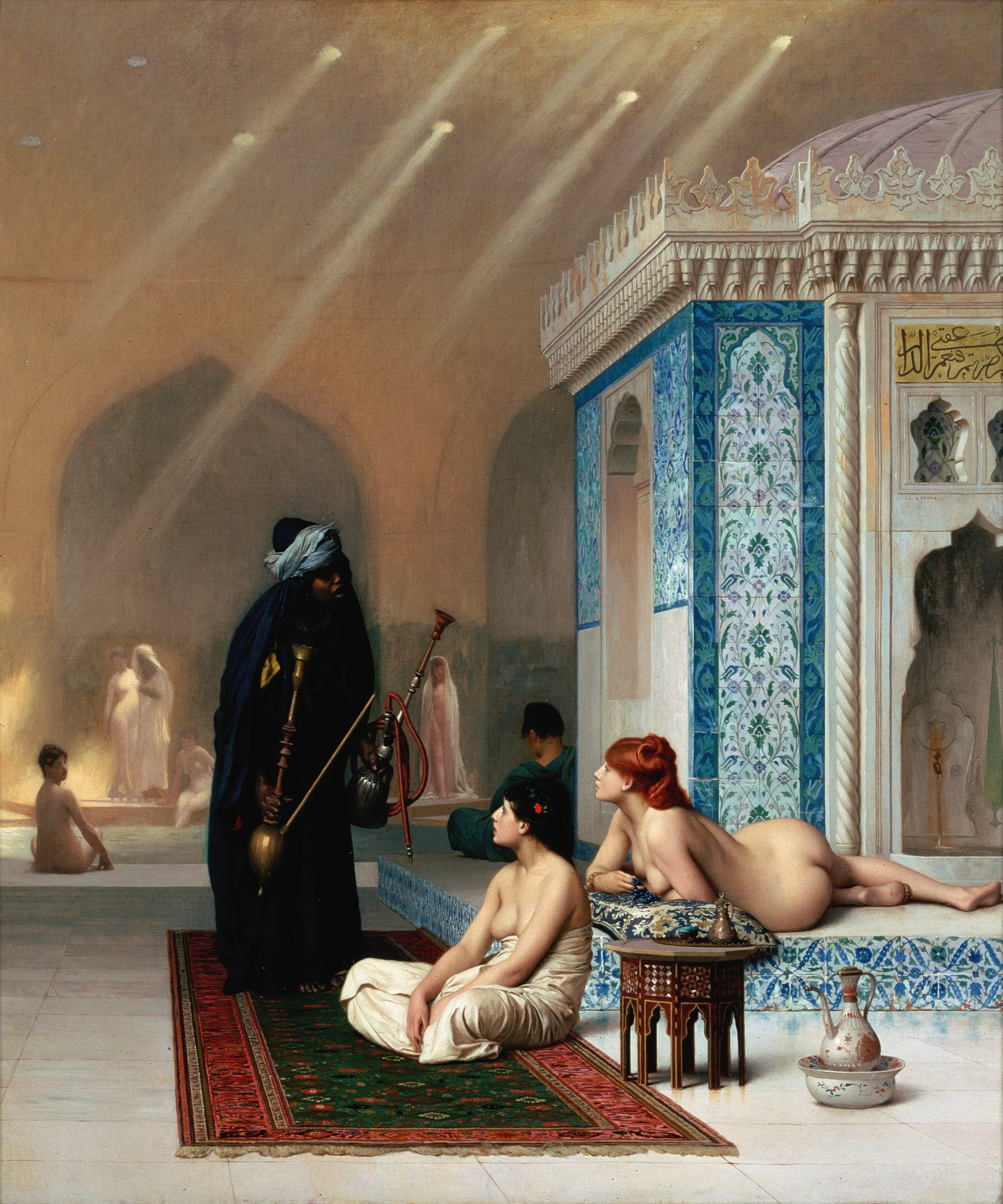

Inside Harem bath by Jean Leon Gerome

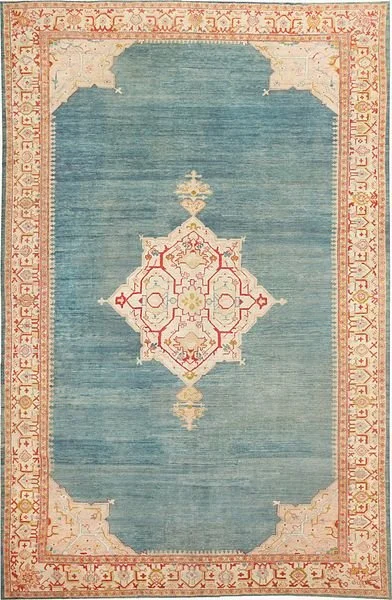

18th Century Turkish Oushak Carpet

Architecture Daily, Blue Oriental Rug

These designs were created to reflect the beauty and wealth that can be found in gardens and pools of palaces and estates. Not surprising, the impact of these designs has on people. Their magnificence is undeniable.

Oriental rugs were introduced to Western Europe thanks to individuals from the military, merchants, and noblemen who were the first to bring these treasures back home. Such encounters were pivotal to the development of Renaissance ideas, arts, and sciences.

They were especially influential to Western European painters who included them in their masterpieces.

Holbein, Lotto, Ghirlandaio, Bellini, Gentile, Crivelli, Memling, as well as Van Eyke and Christus are just some artists who were moved by the magnificence of oriental carpets.

‘Georg Gisze the Merchant’ by Hans Holbein.

Holbein carpet, C-14 dated to 1370–1450 AD.

One of the merchants who traveled to Eastern Europe was Georg Gisze who was so impressed with oriental culture that he commissioned a portrait from German/Swiss painter, Hans Holbein. Holbein’s late gothic style of painting was influenced by artistic trends of Italy, France, the Netherlands, and Renaissance Humanism. These influences gave Holbein a unique aesthetic that made him into one of the greatest portrait painters of the 16th century.

Holbein’s portrait of ‘Georg Gisze’ (from Northern Renaissance painted oil on oak wood) included the intricate details of what a businessman’s workplace of the 16th century would look like (account book, scale, writing utensils, money, etc) as well as an oriental carpet which is characteristically known as a ‘Holbein Carpet’.

‘Holbein Carpets’ feature infinite repeats of small rows of alternating octagons and staggered rows of diamonds. Holbein’s paintings that include carpets are ‘Georg Gisze’, ‘Somerset House Conference’ (1608), and ‘The Ambassadors’.

Lotto rug, first half 17th century, offered at auction 2018

Portrait of a Married Couple Lorenzo Lotto Oil on canvas, 96 x 116 cm c. 1523 - 1524 Saint Petersburg, The State Hermitage Museum

Italian painter, designer, and illustrator, Lorenzo Lotto (born in Venice, Italy in 1480) used deeply saturated colors, bold use of shadow, and a surprising expressive range, from the nearly caricatural to the poetic. Lotto was one of the leading Venetian-trained painters of the earlier 16th century.

Lotto’s carpets have a distinct lacy arabesque pattern that repeats suggesting foliage with branched palmettes that terminate at their ends. These carpets were a favorite in the 16th and 17th century.

They were produced along the Aegean Coast of Anatolia as well as those copied in various areas in Europe including Italy, Spain, and England.

‘The Charity of Saint Anthony’ by Lorenzo Lotto in 1542, (The Basilica di Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Venice, Italy). [‘Lotto’ carpet. 16th century, Turkey. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.].

‘Ghirlandaio Carpet’ (19th Century), Met Museume NY, NYC

The Madonna and Child adored by St Zenobius and St Justus, (c. 1483), Uffizi, Florence

Nicknamed ‘Il Ghirlandaio’ (garland-maker) by his goldsmith father who created metallic garland-like necklaces for women of Florentine, Domenico Ghirlandaio would grow up to be a contemporary painter to Botticelli and Filippino Lippi and have apprentices including Michelangelo. Ghirlandaio’s painting(s) included carpets with an octagon shaped medallion in the center inside a square from which curvilinear designs appear, forming an overall diamond shape. These ‘Ghirlandaio Carpets’ have been woven in the Western Anatolian area since the 16th century.

Madonna and Child Enthroned, late 15th century by Giovanni Bellini

Anatolia late 15th early 16th century Prayer Rug, ‘Keyhole’ Motif

Giovanni Bellini and his brother Gentile’s visit to Istanbul in 1479, inspired the birth of the ‘Bellini Carpet’ design in their paintings. These carpets have a single keyhole motif at the bottom of a larger figure traced in a thin border. At the top end of the borders close diagonally to a point, from which hangs down a ‘lamp’. The design had Islamic significance, and its function seems to have been recognized in Europe, as they were known in English as "musket" carpets, a corruption of "mosque".

Anatolia late 15th early 16th century, Crivelli carpet

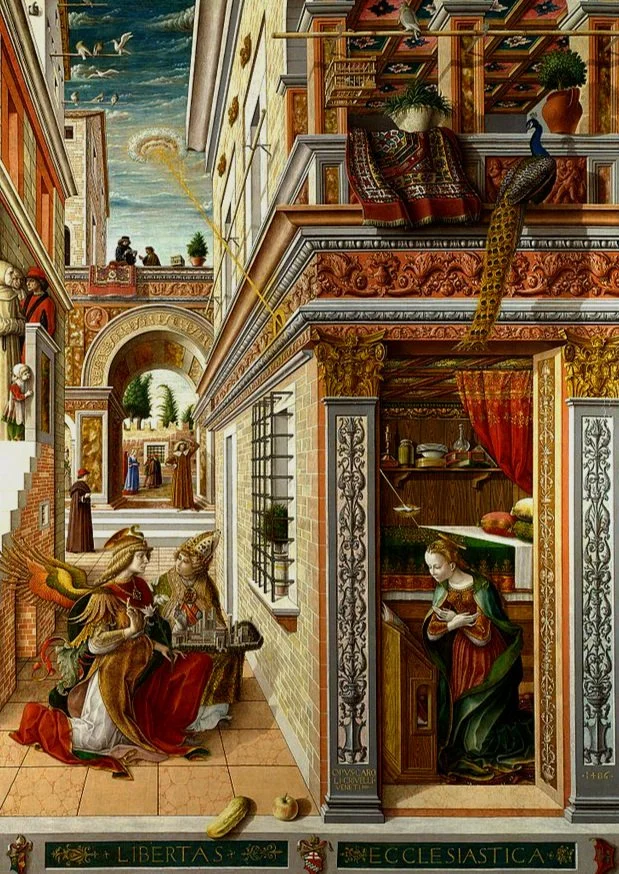

Annunciation with St Emidius, 1486 by Carlo Crivelli.

Carpet designs with a complex 16-pointed star motif made up of many different colored compartments with highly stylized animal motifs are classified as ‘Crivelli Carpets’.

15th-century Venetian painter, Carlo Crivelli painted figures with exaggerated expressions of feeling, that although his paintings overall follow conventions of Renaissance paintings, Crivelli’s figures gravitate more so to the religious intensity of Gothic Art.

Some of Crivelli’s important works are “Madonna della Passione” (c. 1457), in which his individuality is only slightly apparent; a “Pietà” (1485); “The Virgin Enthroned with Child and Saints” (1491), the masterpiece of his mature style; and the eccentric and powerful late masterpiece “Coronation of the Virgin” (1493).

Still Life with a Jug with Flowers, late 15th century, by Hans Memling.

Greatly influenced by Rogier Van Der Weyden, Hans Memling worked in the tradition of early Netherlandish painting and became popular painter in 19th century in Flanders.

Memling carpet’s design were influenced by Armenian carpets from the last quarter of the 15th century. Memling carpets are characterized by several lines that end in ‘Hooks’ coiling in on themselves through 2 or 3, 90° turns.

An example of this can be seen in a miniature painted for Rene of Anjou about 1460. [Hans Memling, Still Life with a Jug with Flowers (The reverse side of the “Portrait of a Praying Man”, c. 1480, Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain.]

Virgin and Child between St James and St Dominic by Hans Memling. (1488–1490) at the Louvre Museum.

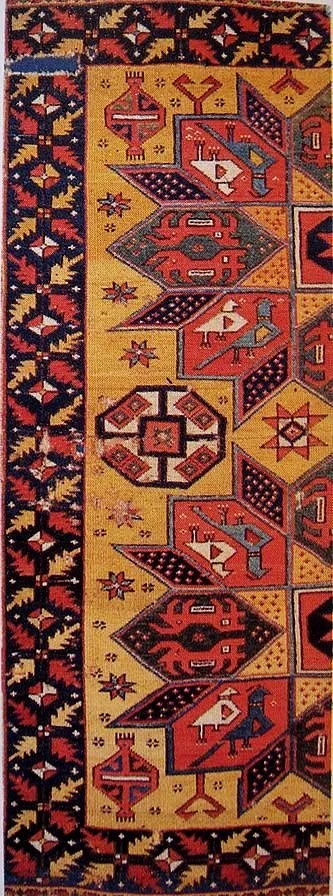

Konya 18th Century Carpet with Memling gul design

Carpets depicted by Jan van Eyck and Petrus Christus could be of Western European manufacture. The undulating 3-fold or trefoil design, a well-known feature of Western Gothic design.

These paintings have a predominantly geometric design with a lozenge composition in infinite repeat, built up from fine bands which connect eight-pointed stars.

These carpets are most like Anatolian carpets from the 17th century.

Jan van Eyck Netherlandish painter painted carpets in his paintings: Paele Madoonoa, Lucca Madonna, and Dresden Triptych.

Lucca Madonna by Jan van Eyck

Triptych of Mary and Child, St. Michael, and the Catherine by Jan van Eyck

Paele Madoonoa by Jan van Eyck

Petrus Christus also a Netherlandish painter included oriental carpet in his ‘Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Jerome and Francis’.

*European paintings helped scholars identify them and eventually developed a dating system based on the paintings they appeared in. The carpets were named after the artist that painted them. The style of carpet depicted would have been the type of carpet the artist was most likely exposed to.

The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints Jerome and Francis (detail), 1457 by Petrus Christus.

Prayer rug, 18th Century, Met Museum, NY, NY.

Despite the conditions that an authentic Anatolian or Turkish rug is discovered, to own one is to be a keeper of history. It is the tangible essence of a rich culture that within it, stores untold tales of adventure, millions of overheard secrets, and stories of the human soul. It radiates an energy impossible to ignore. When placed inside, the rug takes a life of its own. A house transforms into a home. The presence and warmth of inhabitants stir an awakening that no human could possibly name, but the experience is, without question, nothing short of MAGIC.

LINKS:

[A]: https://theculturetrip.com/europe/france/articles/the-top-10-orientalist-artworks/

[B]: https://originsoforientalism.wordpress.com/2016/12/07/blog-post-title-2/

[C]: https://www.christies.com/features/Orientalist-Art-Collecting-guide-8426-1.aspx

[D]: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/440723

[E]: https://www.theartstory.org/movement/orientalism/artworks/

[F]: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vernet-Lecomte_2.jpg